HIV came to NYC at least a decade before virus ID’d

A genetic study of HIV viruses from the 1970s may finally clear the name of a man long identified as the source of the AIDS epidemic in the United States. HIV came to New York City between 1969 and 1973, long before the man known as Patient Zero became infected, researchers report October 26 in Nature.

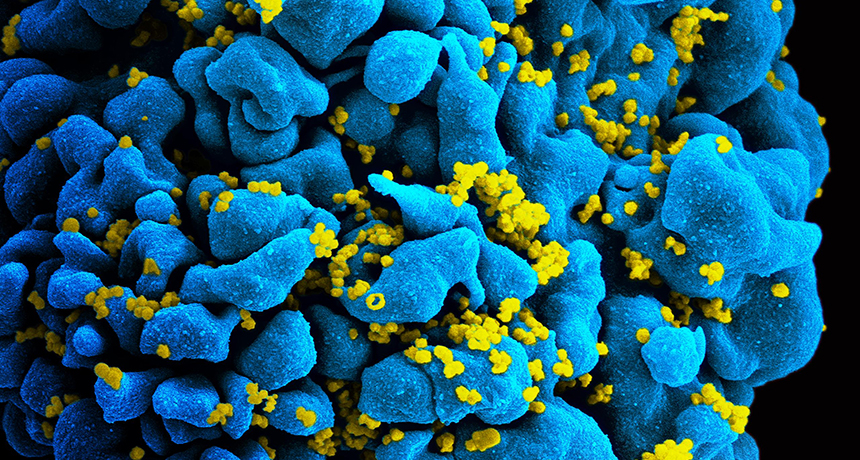

Using techniques developed to decipher badly degraded ancient DNA from fossils, researchers reconstructed the genetic instruction books of eight HIV viruses from blood samples collected in 1978 and 1979 in New York City and San Francisco. The viral DNA was so genetically diverse that the viruses must have been circulating in the cities for years, picking up variations, says evolutionary biologist Michael Worobey of the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Worobey and colleagues calculate that the virus probably first jumped to the United States in 1970 or 1971. So HIV spread for about a decade before AIDS was recognized in 1981 and found to be caused by a retrovirus in 1983.

Examining the relationships between the New York City and San Francisco viruses with HIV strains from elsewhere let researchers trace the virus’s path. The eight American samples all came from the same branch of the HIV family tree as ones from the Caribbean. That suggests that HIV spread from Africa to the Caribbean before making its way to the United States. New York HIV samples were more diverse than those from California, indicating that New York City was probably the hub of early HIV spread and the virus arrived in San Francisco later.

Worobey and colleagues also examined HIV DNA from Patient Zero. Also known as Case 57, he was part a 1984 study of gay men with AIDS in Los Angeles who had either a rare cancer called Kaposi’s sarcoma or Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, both complications of the disease. Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that many of the men had had sexual contact with each other, helping to establish that HIV is sexually transmitted.

Later, in the book And the Band Played On, author Randy Shilts identified Patient Zero as an Air Canada flight attendant named Gaëtan Dugas. It was widely interpreted that Dugas was the first case of HIV in the United States, even though the CDC never claimed — and has repeatedly refuted — that, says epidemiologist James Curran, a coauthor of the 1984 study who is now at Emory University in Atlanta. Part of the confusion may have been that Patient Zero was supposed to be identified as Patient O (for “outside of California”).

Dugas became a flight attendant in 1974 and began traveling to the United States shortly after, says Richard McKay, coauthor of the new study and a medical historian at the University of Cambridge. Dugas estimated that he had about 250 male sexual partners each year between 1979 and 1981. Shilts and others contended that Dugas was intentionally spreading the virus to others, though he was diagnosed with Kaposi’s sarcoma in 1980 before anyone knew what AIDS was or that it was caused by a virus.

Now, the genetic analysis confirms that Dugas was not carrying the earliest version of the virus. “This individual was simply one of thousands infected before HIV/AIDS was recognized,” McKay says.

The new study is a cautionary tale against trying to pin the spread of an infectious disease on any one person, says Robert Remien, a behavioral scientist at Columbia University Medical Center. “There’s no blame or cause to be laid on any of those people in those early years.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated November 10, 2016, to fix the alignment of the timeline with the phylogenetic tree and to update the number of sequential diagnoses in the Patient Zero cluster of AIDS cases.